The Great Plains

First, there was the land itself.

The Great Plains roughly encompasses the land west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, stretching as far north as Canada and as far south as upper Texas. The first Americans to live on this land were the tribes of the Blackfoot, Crow, Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche.

The Great Plains is known for being flat, at least to the eye; in reality there is a wide array of topography, including the Sandhills of Nebraska, the Black Hills of South Dakota, buttes and canyons. But the main element is the tall prairie grasses. And it is a great inland desert, prone to long spells without rain only to be inundated by torrential spring downpours. Winters are notably harsh with blanketing snow. The wind is capricious. Tornado Alley is part of this area.

But it is so enormous in scope, it’s little wonder that the United States was anxious to get it in the Louisiana Purchase. Once it was part of the country, then, the inevitable happened: White people began to settle the territories, in anticipation of them becoming states. But before this began in earnest, the Civil War started in 1861.

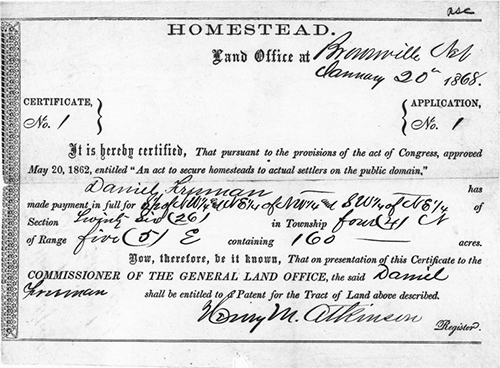

The Homestead Act of 1862

One of the astonishing things to recall is that even while the Union was fighting the Confederacy it was still planning for the expansion of the country. The Homestead Act was in large part a reaction to the war; it explicitly barred anyone who had ever taken up arms against the Union from participating. This ensured that the expanding Union would not include slavery.

President Lincoln signed the act into law in 1862. The Homestead Act basically said that any adult head of a household could apply for a homestead—160 acres of Federally owned land. The land had to be occupied for five consecutive years and proved up (which generally meant farming or ranching and building a dwelling on it). This all had to occur by the end of the 7th year after filing the claim. Once this happened, then, the homesteader was granted the land for only a small filing fee.

The Homestead Act did not discriminate by gender or race; there were female homesteaders and Black homesteaders. However, there was discrimination by those speculators who bought up large tracts of the land and then turned around and sold them, a process that was legal under the act. (In addition to living on and proving up the land, homesteads could also be purchased by corporations or speculators, for a fee out of the reach of most Americans.) The whole idea of the Homestead Act, though, was to provide a way for individual farmers and families to settle the Great Plains—the American ideal of the family farm.

But how were families supposed to reach the land? Of course, there was the wagon train. But the railroad was fast becoming the major way of transportation, the way to connect the entire continent.

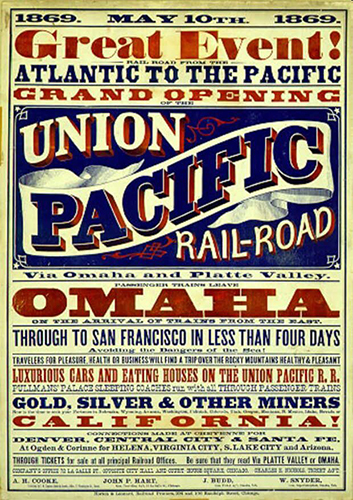

The Transcontinental Railroad

Again, even as the Union was fighting a war, eyes were turned to the expansion of the country. And so the plan to build one railroad connecting the East coast to the West was underway. Between the years of 1863 and 1869, two railroad tracks, one heading west from Council Bluffs, Iowa, and the other starting in San Francisco and heading east to meet it, were constructed, meeting at Promontory Summit, Utah. This railroad truly opened the floodgates of homesteaders heading west. And they were needed. The railroad companies owned the land around the tracks and needed to populate it with railroad depots and towns. They also needed freight and passengers to transport in order to keep the profits coming. So they, along with many of the boosters in the territories, began a propaganda campaign to bring homesteaders to the Great Plains, reaching out to city dwellers in the east, and to Europeans, primarily those residing in Northern Europe. The word was out: The Great Plains was open for business.

But first, they had to do something about the Native Americans living on it.

The American Indian Wars

After the Civil War was over, the United States had a grand army. It also had, in its eyes, a grand problem: The Native Americans living on the Great Plains were defending their land from the increasing waves of homesteaders.

Ever since the first white colonists stepped foot in Jamestown, Virginia, there had been an ongoing war against the Native Americans. Part of Andrew Jackson’s legacy is the tragic Trail of Tears, the diaspora of Native Americans from the southeast to the territories west of the Mississippi. Now those territories were suddenly valuable due to the railroad and the Homestead Act and the discovery of gold in the Black Hills. So something had to be done. Union Generals Phil Sheridan and William Tecumseh Sherman engineered the long war against the Sioux on the Great Plains, including the Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana in 1876, and culminating in the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890.

By 1888, the year of The Children’s Blizzard, most of the great Sioux nation was confined to a reservation encompassing much of South Dakota east of the Black Hills, leaving the rest of the territories for the homesteaders and railroads. This tragedy is one we have yet to fully reckon with still today.

Weather and the beginning of the National Weather Service

When The Children’s Blizzard occurred in 1888, there was no national weather service as we know it today. The Army Signal Corps was in charge of what was called “indicating” the weather. Prior to the blizzard, the Army had just opened up the first headquarters west of the Mississippi, in St. Paul, Minnesota. Previously, through an array of stations scattered across the entire country, either at Army forts or railroad depots, that telegraphed wind and temperature readings at regular intervals throughout the day, the only branch for collecting this data was in Washington, DC. The time it took for the data to arrive, be mapped out, and then an indication pronounced and telegraphed back out to all the stations and newspapers meant that by the time the indications arrived where they could be helpful, the weather had already blown through.

Opening up the St. Paul office meant that the new railroads and the towns that had popped up along them could get more timely warnings of inclement weather. But the system was far from perfect, even considering the primitive tools and science of the time. The Army Signal Corps was rife with corruption. Many of the soldiers in charge of collecting data and relaying it outsourced the job while they went fishing or hunting or otherwise took a break. There was a lot of falsifying—or simply making up—of readings, again, so that the person in charge could be off doing other things. There was a movement to take this increasingly important job away from the Army and put it in the hands of private citizens—scientists who were more experienced, even amateurs who made the study of weather their life’s work—but it remained firmly in the hands of the Signal Corps, for the time being.

Even if the weather—exceedingly hard to predict in the Great Plains; weather much more capricious and ferocious than most of these men had ever experienced back East—could be indicated and warnings issued, most of the homesteaders wouldn’t know it. Indications ran in the large newspapers of the cities like Omaha. And warning flags were raised above train stations. But most homesteaders didn’t live within visual distance of these stations and couldn’t take a daily newspaper on the prairie. So they had to learn how to read the skies themselves. But fronts roaring down from Canada, over the Rocky Mountains that disrupted them into unpredictable patterns, were unlike the fronts most of these Northern European immigrants had ever experienced.

A “Cold Wave” was the worst winter warning that could be issued at the time. The office in St. Paul misread the readings coming in—or they arrived too late—and did not issue a Cold Wave warning prior to the blizzard.

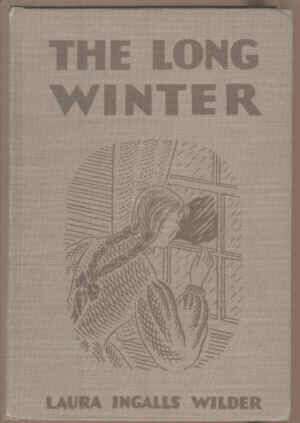

The Little Ice Age

As a child, I was a fan of the Little House on the Prairie books. The book, The Long Winter, always stood out to me as a particularly grim book in the series. This book was about the long winter of 1880-1881, and not The Children’s Blizzard as many people think. But the winters on the Great Plains were unusually harsh during the 1880s, the tail end of the period now known as “The Little Ice Age” which occurred from the 13th through the 19th centuries. From about the turn of the 20th century on, the earth has been slowly warming up.

As a child, I was a fan of the Little House on the Prairie books. The book, The Long Winter, always stood out to me as a particularly grim book in the series. This book was about the long winter of 1880-1881, and not The Children’s Blizzard as many people think. But the winters on the Great Plains were unusually harsh during the 1880s, the tail end of the period now known as “The Little Ice Age” which occurred from the 13th through the 19th centuries. From about the turn of the 20th century on, the earth has been slowly warming up.

The Long Winter depicted by Laura Ingalls Wilder is typical of winters on the Great Plains in this time period; blizzard after blizzard, with only a day or two between. Snow so deep the railroads stopped running, so that food supplies grew perilously low in the prairie towns. Fuel, too, grew scarce; during this time period there weren’t many trees on the prairie for firewood, so cords of hay were used. Sometimes, dried cow patties had to suffice. Homesteaders had to lay in a good supply of food for the winter, but the crops were not reliable in this time period, as even the summers had their challenges—grasshoppers eating crops, prairie fires, drought.

Ranchers, too, suffered. The winter of 1886-1887 (the year prior to The Children’s Blizzard) was known as The Great Die Off because so many cattle were lost. One young Easterner who had tried his hand at cattle ranching in the Dakota territory, Theodore Roosevelt, lost a fortune that year and got out of the business for good, turning his attention to politics instead.

The vast majority of homesteaders weren’t prepared at all for this kind of weather, because they had been promised something else entirely.

Fake News

“Fake News” is a pejorative term today, meant to slander legitimate journalists. But the term could definitely have been applied to the boosters who desperately needed people to settle the Great Plains. In order to lure people to homestead, they hired “journalists” to write propaganda pieces describing these harsh plains as a veritable Garden of Eden with gentle weather and abundant rainfall. These pieces were then planted in newspapers in the East and in countries such as Sweden, Germany and Norway. Many Northern European immigrants came to America on the basis of nothing but these false descriptions, only to arrive ill-equipped to survive, let alone thrive. In the 1880s and 1890s, sixty percent of homesteaders gave up and went back home.

January 12, 1888

The weather prior to the 12th had been unusually cold, even for the Great Plains; temperatures remaining well below zero day and night. Because most prairie children had to walk at least a mile to school, this meant that classrooms had not been in session for several days. The day of the blizzard dawned surprisingly warm, given the past week or so. The temperatures were as high as twenty or thirty degrees above zero; practically balmy for a prairie winter.

The weather prior to the 12th had been unusually cold, even for the Great Plains; temperatures remaining well below zero day and night. Because most prairie children had to walk at least a mile to school, this meant that classrooms had not been in session for several days. The day of the blizzard dawned surprisingly warm, given the past week or so. The temperatures were as high as twenty or thirty degrees above zero; practically balmy for a prairie winter.

This meant that homesteaders went out on the prairie in droves. They rode to town to get much-needed supplies or took livestock out for exercise. And children and their schoolteachers left for the schoolhouse for the first time in days, many of them without their usual heavy cloaks, boots and scarves.

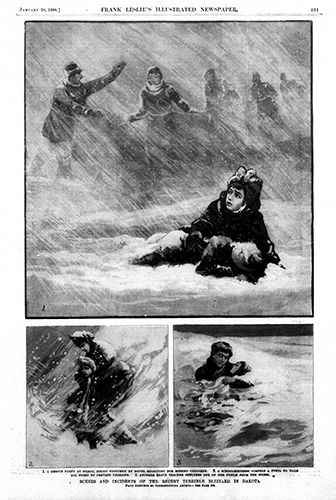

In the early hours of the 12th, a massive Arctic cold front collided with a rush of warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico somewhere over Montana. The resulting explosive blizzard then began to move quickly to the south and east, over the Great Plains, hitting Nebraska and the Dakota Territory right when school was letting out for the day, in the afternoon. Witnesses recounted that it was a terrifying storm, full of electricity—several mentioned frightening wagon wheels of lightning rolling over the prairie and stoves giving off terrifying blue sparks. The wind was fierce, reaching hurricane levels; anyone caught unawares was immediately lost on the prairie with few landmarks like trees or buildings. The snow was unusually dry and gritty so that it clogged every surface and impaired breathing and vision. And rushing behind the storm was a deadly drop in temperature; forty degrees or more.

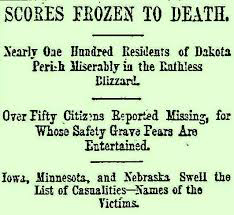

The official death toll is listed at two hundred thirty-five but is thought to be much higher. Many people died weeks or months after the blizzard from infection from frostbite or amputation. And many bodies weren’t found until after the spring thaw.

The Heroine’s Fund

The prairie schoolteacher found herself making a life or death distance in an instant when the storm hit. Should she release the children, and pray they would outrun the storm? Or should she keep them inside and risk freezing or starving to death? The prairie schoolhouse was a poorly insulated dwelling; most districts didn’t have the money to build an adequate structure, especially since children weren’t in it all that much. The fuel ration was generally only adequate for a few hours a day. There was no food beyond what the children had brought for lunch.

Still, most schoolteachers decided to shelter in place, struggling to calm their pupils, to keep them warm, to pray for rescue. These teachers were generally very young, just out of the classroom themselves. The prairie schoolteacher usually did not attend college, not even a two-year teaching college; on the prairie, homesteaders had to fend for themselves and couldn’t afford a teacher with any kind of college education. So most of them were young girls of the district or neighboring districts, many boarding out for the first time, only fifteen or sixteen. Teachers could not be married, which meant that the average age was very young.

But many of those who decided to shelter in place found themselves forced out onto the prairie with their pupils in the worst of the blizzard, when roofs blew off or windows blew out of these rickety structures. Those teachers who got their children to safety in the midst of the storm became heroines. The local newspapers—like the Omaha Daily Bee—were desperate to find good stories out of the tragedy, if only to keep subscribers reading after the initial stories of the storm came out. So the Daily Bee formed what was called “The Heroine Fund,” asking for gifts and donations to a handful of young women they singled out for bravery. One of these, Minnie Freeman, even had a song written in her honor called “Nebraska’s Fearless Maid.”

The Aftermath

While the blizzard did make headlines all across the country, two months later another fierce storm struck the East Coast—New York City and Boston—and soon, most of the country forgot about The Children’s Blizzard. This latter blizzard is widely known as “The Great Blizzard of 1888,” and was the subject of an American Experience episode.

The homesteaders, however, did not forget. Those who survived recounted the horror stories for generations. Many towns held annual reunions of the survivors well into the middle part of the 20th century. In All Its Fury: A History of The Great Blizzard of 1888 in Stories and Reminences was published in 1947. This was an oral history of the storm, full of stories shared by those who survived it.

In the Nebraska State capitol building in Lincoln, a mural depicting Minnie Freeman and her schoolchildren in the storm was installed in 1967, where it remains today.

The Army Signal Corps was soon divested of its weather indicating responsibilities in the aftermath of the two furious blizzards of 1888. (They didn’t get either one of them right.) In 1890 what was then known as the Weather Bureau of the United States was moved to the Department of Agriculture, then to the Department of Commerce in 1940, and then renamed The National Weather Service in 1970.

With today’s technology—text alerts for every weather warning, sophisticated satellite imagining, and more importantly, perhaps, over a hundred years of recorded weather data to draw on—it’s difficult to imagine how a single blizzard could take so many people by surprise and result in so many deaths, so many millions of dollars in destruction. We take the weather for granted, almost, these days. We know we can get to shelter if we need to, because we have plenty of warning, we have cars to take us where we need to go, school buildings are structures built to withstand most weather, kids don’t walk a mile or two to get to them. We know days in advance before a storm strikes so we can stock up on canned goods and toilet paper. A snow day is a welcome vacation.

But the next time a blizzard hits, it might be interesting to walk outside in just a sweater or a jacket and imagine yourself all alone on the prairie, with no idea where you are or how to get to any kind of shelter. Then you’ll know, at least a tiny bit, how it felt to be caught in The Children’s Blizzard.