The Morrow Family

Anne Spencer Morrow was born on June 22, 1906, in Englewood, New Jersey into a distinguished family. Her father, Dwight W. Morrow, was a partner at J. P. Morgan and civilian adviser to generals and presidents; he was invited by his schoolmate, Calvin Coolidge, to head up a board that eventually led to the establishment of the U.S. Army Air Corps. He later was appointed Ambassador to Mexico, and served as the Republican senator from New Jersey. Anne’s mother, Elizabeth Cutter Morrow, was a poet in her youth who immersed herself in her husband’s career and proved to be a tireless committee woman; she was appointed to fill an interim vacancy as President of Smith College, her alma mater, in 1939. As such, she became the first woman head of Smith. The Morrow family enjoyed a life of wealth and privilege, although the parents also instilled a sense of duty in their children. Despite the privilege, the family had its share of misfortunes. Elisabeth, Anne’s glamorous, brilliant older sister, suffered from a heart condition that ended her life prematurely. Anne’s brother, Dwight, was mentally fragile and suffered a series of breakdowns. Still, Anne’s upbringing allowed her to travel the world at a young age, provided her the best education a woman of her time could expect, and brought her face to face with the greatest hero of her generation, Charles Lindbergh.

Anne Spencer Morrow was born on June 22, 1906, in Englewood, New Jersey into a distinguished family. Her father, Dwight W. Morrow, was a partner at J. P. Morgan and civilian adviser to generals and presidents; he was invited by his schoolmate, Calvin Coolidge, to head up a board that eventually led to the establishment of the U.S. Army Air Corps. He later was appointed Ambassador to Mexico, and served as the Republican senator from New Jersey. Anne’s mother, Elizabeth Cutter Morrow, was a poet in her youth who immersed herself in her husband’s career and proved to be a tireless committee woman; she was appointed to fill an interim vacancy as President of Smith College, her alma mater, in 1939. As such, she became the first woman head of Smith. The Morrow family enjoyed a life of wealth and privilege, although the parents also instilled a sense of duty in their children. Despite the privilege, the family had its share of misfortunes. Elisabeth, Anne’s glamorous, brilliant older sister, suffered from a heart condition that ended her life prematurely. Anne’s brother, Dwight, was mentally fragile and suffered a series of breakdowns. Still, Anne’s upbringing allowed her to travel the world at a young age, provided her the best education a woman of her time could expect, and brought her face to face with the greatest hero of her generation, Charles Lindbergh.

The Lindberghs

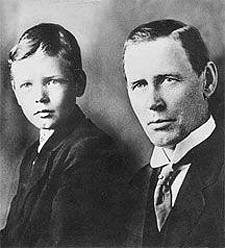

Charles Augustus Lindbergh was born on February 4, 1902, in Detroit, Michigan. His father, Charles August Lindbergh, was a Swedish immigrant who later served as a U.S. Congressman from Minnesota; his career ended when he opposed U.S. entry into World War I. Charles’s mother, Evangeline Lodge, was a schoolteacher. The family moved to Little Falls, Minnesota, spending some time in Washington DC during his father’s terms in Congress even though Charles August Lindbergh separated from his wife in 1909. Charles’ upbringing was very different from Anne’s; he was an only child (he had two stepsisters from his father’s first marriage, but they were estranged from his mother); and his mother, who practically raised him alone, worked during his childhood. Charles Lindbergh was not a great student; he dropped out of the University of Wisconsin in the middle of his sophomore year in order to learn how to fly.

Charles Augustus Lindbergh was born on February 4, 1902, in Detroit, Michigan. His father, Charles August Lindbergh, was a Swedish immigrant who later served as a U.S. Congressman from Minnesota; his career ended when he opposed U.S. entry into World War I. Charles’s mother, Evangeline Lodge, was a schoolteacher. The family moved to Little Falls, Minnesota, spending some time in Washington DC during his father’s terms in Congress even though Charles August Lindbergh separated from his wife in 1909. Charles’ upbringing was very different from Anne’s; he was an only child (he had two stepsisters from his father’s first marriage, but they were estranged from his mother); and his mother, who practically raised him alone, worked during his childhood. Charles Lindbergh was not a great student; he dropped out of the University of Wisconsin in the middle of his sophomore year in order to learn how to fly.

Early Aviation

Just a year after Charles Lindbergh was born, the Wright brothers made the first powered and engineered human flight of an airplane in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, ushering in the golden age of aviation. Immediately the country, and the world, was caught up in the romantic notion of flight; the most celebrated heroes of World War I were the dashing flying aces of both sides of the conflict. In the 1920s, barnstorming pilots crossed the nation performing stunts and taking up daring customers for rides, and air mail pilots were heroes just as the Pony Express riders had been. Charles Lindbergh began barnstorming in 1922; he became a 2nd lieutenant in the Air Service Reserve Corps in 1925, in 1926 he was flying out of Lambert Field of St. Louis as an air mail pilot.

The Orteig Prize

In 1919, Raymond Orteig, a hotel owner, offered $25,000 to the first aviator or aviators to fly nonstop from New York to Paris, or vice versa. The prize was only offered to aviators from the allied countries of World War I. No one competed for the prize for five years, primarily because aviation wasn’t yet technically advanced enough; in 1924, Orteig renewed the prize for another five years. Several aviators tried unsuccessfully; some were killed in the pursuit of the prize. Charles Lindbergh, a young airmail pilot, conceived of a way to fly solo, which was thought almost suicidal; the trip would take more than 30 hours. But with the backing of a consortium of St. Louis businessmen, The Spirit of St. Louis was manufactured by Ryan Airlines of San Diego. A single-engine plane designed for only one, Lindbergh insisted all non-essential equipment—like a parachute—be left out in order for the plane to carry as much fuel as possible.

In the early morning of Friday, May 20, 1927, Lindbergh and The Spirit—which Lindbergh always referred to as “WE,” himself and the aircraft as one—took off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York. As the world held its breath, he flew across the ocean alone; 33.5 hours later he landed at Le Bourget Air Field outside of Paris at 10:22 PM on Saturday, May 21st. Newsreel cameras captured both the takeoff and landing; when “WE” landed, 150,000 spectators mobbed the airfield, nearly ripping the plane—and Lindbergh—to shreds. He was instantly the most famous American in the world, a shy, handsome 25-year-old hero who had done the impossible.

After the trip, he was presented with every medal imaginable, feted with a ticker tape parade in New York City, and became the face of aviation. He took The Spirit on a tour of the 48 United States, culminating in a goodwill tour to Mexico in December of 1927. There, he met Anne Morrow, the daughter of the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico.

Watch a silent video of Lindbergh’s Flight and Return:

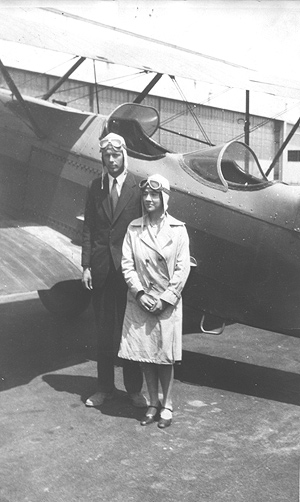

The First Couple of the Air

In marrying Charles Lindbergh, Anne Morrow traded a quiet, bookish life for one of fame and adventure. Charles taught her to fly and in 1930, she became the first U.S. woman to earn a glider pilot’s license. She eventually earned her own pilot’s license, mastered navigation and radio operation, and co-piloted the most famous aviator of all time on record-breaking trips. They broke speed records, mapped flight paths that are still used today and became the faces of TAT (Transcontinental Air Transport), which was the first passenger airline to offer trans-continental service.

In marrying Charles Lindbergh, Anne Morrow traded a quiet, bookish life for one of fame and adventure. Charles taught her to fly and in 1930, she became the first U.S. woman to earn a glider pilot’s license. She eventually earned her own pilot’s license, mastered navigation and radio operation, and co-piloted the most famous aviator of all time on record-breaking trips. They broke speed records, mapped flight paths that are still used today and became the faces of TAT (Transcontinental Air Transport), which was the first passenger airline to offer trans-continental service.

Anne’s first success as a published author was the bestselling North to the Orient, which beautifully chronicled their first survey flight across the Arctic Circle to Japan. She was able to write about aviation in a way that captured the public’s imagination without being too technical; she focused on the human aspect of flight, the people she met on their journeys.

The Smithsonian Institute’s National Air and Space Museum has an exhibit devoted to both Charles and Anne Lindbergh, giving Anne her due credit for her role in pioneering aviation.

The Crime and Trial of the Century

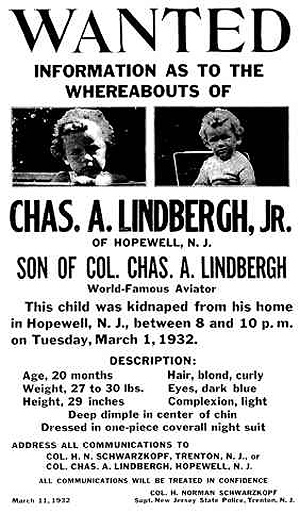

In 1932, the world was horrified by the kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh, Jr., only twenty months of age.

In 1932, the world was horrified by the kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh, Jr., only twenty months of age.

After marrying Charles Lindbergh, Anne found herself thrust, unwillingly, into the harsh glare of the spotlight. Young, glamorous, heroic, the Lindberghs captured the heart of not just America, but the whole world. Songs were written about them, newspaper articles invented about them. People knocked on their door just for a glimpse; in order to enjoy any kind of normal life, they sometimes resorted to wearing disguises in public (to little success). Newsreel cameras were present at any event they attended; maps drawn to their new home outside of Hopewell, New Jersey. And when Anne gave birth in June 1930 to their firstborn, Charles Lindbergh Jr., the “Little Eaglet,” as he was called (after his father’s nickname, “The Lone Eagle”), became the world’s most famous baby.

On the evening of March 1, 1932, Charles Lindbergh Jr. was kidnapped from the Lindberghs’ new home outside of Hopewell. The Lindberghs had not fully moved in; their habit was to stay there on the weekends, then travel back to Englewood where they lived with Anne’s family. It was unusual for them to stay over on a Tuesday night, but the baby had a cold and Anne was reluctant to move him. With them in the home were the baby’s nurse, Betty Gow, and a couple who took care of the house in their absence, Ollie and Elsie Whately.

When Betty Gow discovered the baby was missing from his crib, the household searched frantically, finding an envelope inside the nursery. Lindbergh called the police; within minutes members of the Hopewell police and the New Jersey State police were scouring the grounds for clues, unfortunately trampling most of what evidence there was. The envelope was opened and found to contain a ransom note.

Immediately the house became the center of a media frenzy; reporters, sightseers, police swarmed upon it. Radio—just beginning to be found in every household in the land—kept the entire country updated with periodic bulletins. Boy Scouts throughout the nation knocked on doors searching for the baby; cars with any children in them were stopped and searched by police.

The search for the baby became a surreal circus, with many charlatans and opportunists claiming to know what had happened to the child. Charles Lindbergh left nothing to chance; he interviewed everyone, even, at one point, using members of the New York syndicate as emissaries to the kidnappers.

Over two months later, Charles Lindbergh Jr.’s body was found less than five miles from the house. It was suspected that he had died almost immediately.

Suspicion initially focused on members of the Lindbergh and Morrow household staff. The trail seemed to grow cold, as no arrests were made. Then, in September of 1934, Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a German immigrant with a criminal record, was arrested and charged with the crime; pieces of wood used in the construction of a ladder found at the kidnapping scene were discovered in his garage, and marked gold certificates that had been paid as ransom were traced back to him.

After a highly-publicized trial—”The Trial of the Century”—Hauptmann was found guilty of the murder of Charles Lindbergh Jr., and was executed in 1935. To this day, there are those that remain unconvinced that Hauptmann was involved.

America First

After the murder of their firstborn, Charles and Anne, along with the child Anne had been carrying when Charles Jr., was kidnapped, Jon, left the United States for Europe. There had been threats on Jon’s life, and the hounding by the press—which they blamed for the death of little Charlie—only intensified. They first moved to England, then to an island off the coast of France. They also thought seriously of moving to Nazi Germany, where the chancellor, Adolph Hitler, promised them complete protection from any press.

At the urging of the U.S. military, the Lindberghs visited Germany to report on the buildup of the air force. While there, they attended the Opening Ceremonies of the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin as guests of Hermann Goering. They did not meet Adolph Hitler, although they were seated near him. During this visit Goering presented Charles with the Service Cross of the Gold Eagle on behalf of his aviation accomplishments; this was only one of many international medals Charles had been presented.

But the world was on the brink of war, and America had not quite forgiven the Lindberghs for fleeing the country for Europe. The German medal became more and more of a liability when they moved back to America in 1939.

In late 1940, Charles Lindbergh became the face and voice of the America First Committee, a committee dedicated to keeping America out of the European conflict. At first, the majority of Americans were against going to war, and America First was popular. But as the war raged on, and Britain was bombed, the mood of the nation turned. Charles Lindbergh became more and more outspoken about his beliefs that the northern European races should not be fighting each other, as they were the natural leaders of the world. Charles blamed President Roosevelt and Great Britain for agitating for American involvement against the Germans and Hitler, many of whose policies he admired, despite his abhorrence of the violence of Krystallnacht. And Charles, despite Anne’s pleadings not to, finally spoke of a third group whom he blamed for trying to get America into the war — the Jewish people.

Anne, at his urging, wrote a pamphlet in 1940 called The Wave of the Future, in which she tried to explain their beliefs. But in publishing this, Anne alienated many of her friends and family. The Lindberghs were pariahs.

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, America First disbanded and Charles tried to report for duty (he had resigned his commission in the Army). Roosevelt refused to allow him to reenlist. Yet Charles eventually spent the war years working first for Ford, then for Lockheed and other airplane manufacturers, helping to design and test high-altitude planes, even going to the Pacific to train pilots. He was sent to Germany to inspect the captured rocket program, and there he visited the newly-liberated concentration camps; Charles wrote despairingly, first to Anne, then for publication, of his horror at what technology, which he had formerly embraced as “the wave of the future,” had wrought.

Authentic History: A website about America First

Later Years

The Lindberghs led increasingly separate lives from the 1950s on. Charles worked for Strategic Air Command and served on the board of Pan American airlines; he was constantly traveling for work. Anne raised their children and enjoyed the success of Gift from the Sea; in 1969, she published her last original work, Earth Shine, a meditation of life on earth, and man’s journey to the moon. She and Charles both admired the accomplishments of NASA and the astronaut program.

But Charles increasingly turned his back on technology, embracing environmental causes. He continued his travels. Anne turned to other friendships for solace. When, in 1974, Charles died of leukemia and was buried in Hawaii, he left space for his wife to be buried next to him.

Anne, who lived until 2001, continued to lend her name and presence to organizations that protected Charles’s legacy and furthered the causes she and Charles had embraced. The Charles A. and Anne Morrow Lindbergh Foundation is perhaps the best known of these.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh died at the age of 91 on February 7, 2001. Instead of being buried next to her husband, she left instructions for her ashes to be scattered at private locations.